If you manage a Linux server, chances are you use SSH to connect. Attackers are aware of this as well. As soon as port 22 is open to the internet, bots will start trying to break in with brute-force login attempts. I have seen servers get thousands of these attempts just hours after going online.

Weak passwords, outdated cryptography, or careless configurations can transform these attempts from a nuisance to a nightmare. Data breaches, ransomware, or your server becoming a launching pad for other attacks are all real possibilities when your SSH security falls short.

This is why securing SSH should be a top priority, not something you put off. It is one of the most important first steps in making any server safer. The best part is that with just a few configuration changes, you can greatly reduce your risk and make it very hard for attackers to get in.

By the end of this guide, you will be ready to apply these steps and secure your SSH setup right away. Take action on each recommendation as you read to strengthen your server’s defenses.

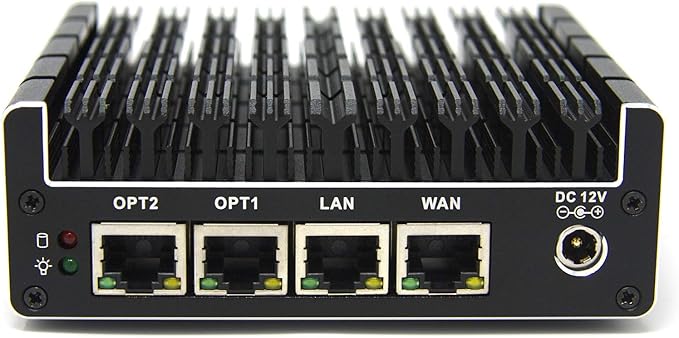

Protectli FW6C/FW6D This fanless firewall appliance is designed for pfSense and OPNsense, providing strong SSH security for homelabs or media servers exposed to the internet. With Intel NICs and hardware AES-NI, it delivers fast, secure routing and supports robust firewall rules, meeting SSH security best practices. It is recommended for anyone looking to secure remote access.

Contains affiliate links. I may earn a commission at no cost to you.

Step 1: Generate a Secure SSH Key Pair

Password authentication over SSH is like leaving your house key under the doormat. Sure, it works, but every bot on the internet is happy to spend all day guessing your password. Key-based authentication, on the other hand, is practically unbreakable when you use modern algorithms.

To setup key-based authentication, you will need to create the keys. This works on Linux and Windows.

Run this on your client machine to create the key pair:

ssh-keygen -t ed25519

The ed25519 algorithm generates keys that are both smaller and more secure than the older RSA standard. If you’re stuck on an older system that doesn’t support ed25519, fall back to this:

ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096

This command creates two files: a private key (which you guard with your life) and a public key (which you can share freely). By default, both keys land in your repesctive .ssh folder (~/.ssh/ on Linux and C:\Users\UserName\.ssh on windows).

Step 2: Deploy Your Public Key to the Server

Now you need to tell the server to trust your public key.

Automatic method (the easy way):

ssh-copy-id user@server_address

This command does all the heavy lifting for you. It copies your public key and adds it to the right place on the server.

Manual method (when you want control):

- Copy the contents of your

~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pubfile - Append it to the server’s

~/.ssh/authorized_keysfile

Here’s the thing: your first login will still need your password because the server hasn’t seen your key yet. But once this setup is complete, you can disable password authentication entirely. After this, your server will be more secure, and you’ll never have to remember another password for SSH access.

MINISFORUM MS-A2 With powerful networking (dual 10GbE SFP+ and dual 2.5GbE), this mini-workstation is perfect for running secure SSH servers and experimenting with advanced SSH configurations in a homelab environment. Its flexible storage and high performance make it a great platform for learning and implementing SSH key authentication and best practices. Ideal for both beginners and advanced users looking to build powerful servers in a compact unit.

Contains affiliate links. I may earn a commission at no cost to you.

Step 3: Secure the SSH Configuration

The real power of SSH security lies in its configuration file at /etc/ssh/sshd_config. This is where you harden your SSH entry point, raising the bar high enough that attackers will abandon their efforts and seek softer targets instead.

Open it with:

sudo nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

Here are the most important changes that harden your SSH setup:

Disable password authentication

This kills brute force attacks dead in their tracks.

PasswordAuthentication no

Disable root login

Never let root log in directly through SSH. Log in as your regular user and escalate with sudo when needed.

PermitRootLogin no

Change the SSH port (optional)

Moving off port 22 cuts down on automated bot noise, though it won’t stop a determined attacker.

Port 2222

If you change this, remember to update your firewall rules accordingly.

Enforce modern encryption

Force SSH to use strong ciphers and message authentication codes, preventing fallback to weaker algorithms.

Ciphers aes256-ctr,aes192-ctr,aes128-ctr

MACs hmac-sha2-256,hmac-sha2-512

Restrict user access

Limit SSH access to specific users or groups instead of allowing everyone:

AllowUsers youruser

After making these changes, restart the SSH service to apply them:

sudo systemctl restart ssh

Your SSH configuration is now significantly more secure than the defaults. These settings create multiple layers of protection that work together to prevent unauthorized access.

Step 4: Set Correct File Permissions

SSH has strong opinions about file permissions, and it’s not shy about letting you know when they are wrong. If your .ssh directory or files are too permissive, SSH will flat-out refuse to use them. Think of it as SSH’s way of protecting you from yourself.

Here are the correct permissions:

chmod 700 ~/.ssh

chmod 600 ~/.ssh/id_ed25519

chmod 644 ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

chmod 600 ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

Breaking this down:

700on the.sshdirectory means only you can read, write, or enter it600on private keys means only you can read or write them644on the public key allows others to read it (which is fine, it’s public after all)600onauthorized_keyskeeps it private to your account

If you’re getting “bad owner or permissions on .ssh/config” errors, these permission settings will almost certainly fix the problem. SSH is particular about security, but once you get the permissions right, it’ll work reliably.

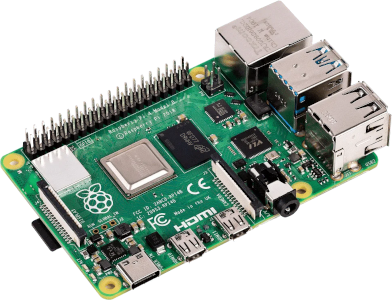

RaspberryPi 4GB The Raspberry Pi 4GB is an affordable, low-power option for learning and practicing SSH hardening techniques in a real-world environment. It’s perfect for beginners who want to set up secure remote access, experiment with public/private key authentication, and test firewall rules before deploying them on larger servers. Its versatility makes it a staple for any homelab enthusiast focused on security.

Contains affiliate links. I may earn a commission at no cost to you.

Step 5: Harden Network Access

Congratulations! Your SSH service is now using keys and more secure settings. But if attackers can reach it from anywhere on the internet, you still need more barriers. Think of it like having a great lock on your front door but leaving avalible for anyone to knock on.

Firewalls

Limit SSH access to specific IPs where possible. This is your first line of defense. Example using UFW (Uncomplicated Firewall):

sudo ufw allow from 203.0.113.10 to any port 2222

VPN or Bastion Host

Place SSH behind a VPN. This will prevent the whole internet from probing all your machines. Only machines that are on the VPN can see the host.

Fail2ban

This tool scans logs and automatically bans IPs showing malicious behavior, like repeated failed login attempts. On Debian/Ubuntu:

sudo apt install fail2ban

Then configure Config Breakdown/etc/fail2ban/jail.local for sshd. Even if you’ve disabled passwords, Fail2ban still helps block port scanning noise and keeps your logs cleaner. It’s like having a bouncer who remembers troublemakers and won’t let them back in.

➤ A good Fail2Ban Starting Config for SSHD

[DEFAULT]

# Whitelist: your trusted networks and admin IPs that should never be banned.

# Replace the placeholders with your real IPs/subnets.

ignoreip = 127.0.0.1/8 ::1 192.168.1.0/24 10.0.0.0/24

# How long to ban an offender (and enable incremental bans).

bantime = 1h

bantime.increment = true

bantime.factor = 2

bantime.maxtime = 1w

# How far back to count failures, and how many failures trigger a ban.

findtime = 10m

maxretry = 5

# Use the systemd journal for log parsing.

backend = systemd

# Use nftables if your distro uses it. Fall back to iptables if needed.

banaction = nftables-multiport

# -----------------------------------

# SSH JAIL

# -----------------------------------

[sshd]

enabled = true

filter = sshd

# If you changed the SSH port, reflect it here (e.g., port = 2222).

port = ssh

# Mode “aggressive” catches more patterns (invalid users, many auth noise cases).

# Requires fail2ban 0.11+ with newer sshd filter.

mode = aggressive

[DEFAULT] block: Sets global behavior all jails inherit.

ignoreip keeps your admin workstation/VPN/LAN from getting locked out during fat-finger moments.bantime, findtime, and maxretry control the ban policy. Here: 5 bad tries within 10 minutes → ban. A 1-hour ban is long enough to stop bots but short enough to forgive honest mistakes.bantime.increment = true (+ factor, maxtime) makes repeat offenders stay banned longer (1h → 2h → 4h … up to 1 week). This crushes persistent botnets without you micromanaging lists.backend = systemd reads from the journal instead of plain log files. It’s resilient to log rotation, works well on Debian/Ubuntu, and behaves nicely in containers/VMs.banaction = nftables-multiport uses nftables rules to block offenders. If your host still uses iptables, switch to iptables-multiport.[sshd] jail: The actual protection for SSH.

enabled = true turns it on.filter = sshd tells Fail2ban which regex set to use. It recognizes failed logins, invalid users, etc.port = ssh binds bans to your SSH port. If you run SSH on a non-standard port, change it (e.g., 2222).mode = aggressive expands matches to catch more brute-force patterns and “invalid user” noise attackers use to enumerate accounts.

Step 6: Test and Verify

Now comes the moment of truth. Before you close that original SSH session (your safety net), let’s make sure everything actually works:

- Open a new terminal window and test logging in with your key.

- Confirm you can’t log in as root.

- Confirm password login is refused.

- Check logs with:

sudo tail -f /var/log/auth.log

This is where patience pays off. Only after confirming everything works should you close your original session. If something breaks, you’ll still have that old session open to fix it. Trust me, there’s nothing quite like the sinking feeling of being locked out of your own server because you skipped this step.

Step 7: Ongoing Monitoring and Auditing

SSH hardening isn’t a one-and-done deal. Think of it like home security: you don’t install locks and never check them again. Attackers adapt their methods, which means your defenses need regular attention too.

Here’s what to keep an eye on:

- Review logs regularly (

/var/log/auth.logorjournalctl -u ssh). Look for failed login attempts, especially repeated ones from the same IP addresses. - Audit authorized keys at least monthly. Remove old keys, particularly when team members leave or change roles. Stale keys are like forgotten spare house keys under the doormat.

- Check for anomalies like new user accounts you didn’t create or SSH configuration changes you didn’t make. These could signal that someone’s already gotten in.

- System Updates keep the server patch and updated. SSH is patch frequently.

Set a calendar reminder to do this monthly. It takes maybe 10 minutes, but catching problems early beats dealing with a breach later.

Troubleshooting Common SSH Problems

Even experienced admins lock themselves out occasionally. Here are the most common ways things go sideways and how to fix them:

-

Locked out after disabling passwords

This classic mistake happens when your SSH key wasn’t copied correctly before you disabled password authentication. You’ll need to access your server through your hosting provider’s web console or rescue environment, then re-enablePasswordAuthentication yesin your SSH config until you get your keys working properly. -

Wrong file permissions

If you see errors like “bad owner or permissions on .ssh/config”, your SSH files are readable by other users, which SSH considers a security risk. Reset the permissions as shown in Step 4 above. -

Forgot to update firewall when changing port

Changed your SSH port toPort 2222but forgot to open that port in your firewall? Your connection will just hang there, looking like a network issue. Always update your firewall rules before changing SSH ports, not after. -

Trying to allow root login with keys

Even with “key-only” authentication, allowing direct root login creates unnecessary risk. If someone compromises your key, they have immediate root access. Stick withPermitRootLogin noand usesudoinstead. -

VPN misconfiguration

If you’re routing SSH through a VPN, test your access thoroughly in a non-production environment first. This setup adds complexity that can leave you stranded if misconfigured.

ASROCK Mini-Desktop Computer This compact barebone system is ideal for running lightweight VMs or containers, allowing you to isolate and secure SSH services as recommended in the guide. Its support for modern Intel CPUs and flexible storage options make it a practical choice for building a secure, dedicated SSH gateway or jump box. Perfect for DIYers who want a tidy, efficient, and secure homelab setup.

Contains affiliate links. I may earn a commission at no cost to you.

FAQs: Secure SSH in Practice

➤ How do I generate a secure SSH key pair?

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 for modern systems. If you’re stuck with older infrastructure, fall back to ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096. The Ed25519 algorithm is faster, more secure, and generates smaller keys, but RSA with 4096 bits still does the job when needed.➤ Why does SSH complain about bad owner or permissions?

.ssh directory needs 700 permissions (owner read/write/execute only), private keys need 600 (owner read/write only), and public keys need 644 (owner read/write, others read). SSH refuses to work with loose permissions because anyone who can read your private key can impersonate you.➤ How do I change the SSH port safely?

/etc/ssh/sshd_config and set Port 2222 (or whatever port you prefer). Here’s the critical part: update your firewall rules to allow the new port before restarting SSH. Otherwise, you’ll lock yourself out and need console access to fix it. Test the new port works before closing your current session.➤ What are the most important `sshd_config` settings?

PasswordAuthentication no (forces key-based auth), PermitRootLogin no (eliminates the highest-value target), strong Ciphers and MACs (modern crypto only), and AllowUsers or AllowGroups (whitelist who can even attempt to connect). These settings alone will block most automated attacks.➤ Is it safe to allow root login with SSH keys?

➤ Should I still use RSA keys?

➤ What extra steps if SSH must face the internet?

➤ How do I set up Fail2ban for SSH?

sshd jail in /etc/fail2ban/jail.local. The default settings work well for most setups: they’ll ban IPs after a few failed attempts and gradually increase ban times for repeat offenders. Just make sure you whitelist your own IP addresses first.➤ What ciphers and MACs should I use?

aes256-ctr for encryption and hmac-sha2-256 for message authentication. Avoid anything with “md5” or “sha1” in the name, and definitely skip older ciphers like 3DES or Blowfish. When in doubt, let SSH negotiate the strongest common algorithm between client and server.➤ How do I recover access if I'm locked out?

/etc/ssh/sshd_config, restart the SSH service, and test from another session before logging out. This is why you always test configuration changes before closing your current SSH session.Conclusion

If you take one thing from this guide, it’s this: SSH security depends less on any one trick and more on layers of defense. Keys instead of passwords, no root logins, careful configuration, restrictive firewalls, monitoring, and automation all stack together to drastically lower your risk.

Set aside a little time to secure SSH right after deploying any new server. It will save you headaches down the line, whether you’re running a personal project or a company’s production infrastructure. Trust me, dealing with a compromised server is far worse than spending 30 minutes hardening SSH upfront.

Next steps you can explore:

- Automating SSH hardening with configuration management tools like Ansible.

- Adding multi-factor authentication for SSH.

Your SSH server should no longer feel like a liability. It should feel like a fortress that you actually trust to keep the bad guys out.